Rapid Burial

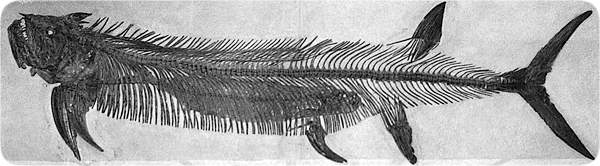

Burial and fossilization must have been quite rapid to have preserved a fish in the act of swallowing another fish. Thousands of such fossils have been found.In the belly of the above 14-foot-long (4.3m) fish is a smaller fish, presumably the big fish’s breakfast. Because digestion is rapid, fossilization must have been even more so.

This delicate, 1 1/2-foot-long wing (46cm) must have been buried rapidly and evenly to preserve its details. Imagine the size of the entire dragonfly!

More than 500 giant fossilised oysters were found 3000 metres (about 2 miles) above sea level in Peru in 2001 by Arturo Vildozola, palaeontologist with the Andean Society of Paleontology.

Fossils crossing two or more sedimentary layers (strata) are called poly- (many) strate (strata) fossils. Consider how quickly this tree trunk in Germany must have been buried. Had burial been slow, the tree top would have decayed. Obviously, the tree could not have grown up through the strata without sunlight and air. The only alternative is rapid burial. Some polystrate trees are upside down, which could occur in a large flood. Soon after Mount St. Helens erupted in 1980, scientists saw trees being buried in a similar way in the lake-bottom sediments of Spirit Lake. Polystrate tree trunks are found worldwide. (Notice the 1-meter scale bar, equal to 3.28 feet, in the center of the picture.)

Frozen Mammoths

The mammoths lived in a sub-tropical climate

There is abundant evidence that the earth once enjoyed a uniformly warm climate. Coal seams in the polar regions show that lush forests once grew where now there is only snow and ice. A fallen 90-foot fruit tree, with ripe fruit and green leaves still on its branches, has been found in the frozen ground of the New Siberian Islands, where only 1-inch high willows grow now. Palm tree fossils have been found in Alaska. Grasses, bluebells, butter-cups and wild beans as fresh as the day they were eaten, have been found in the mouths and stomachs of the frozen mammoths.The most famous, accessible, and perhaps studied mammoth is a fifty-year-old male, found in a freshly eroded bank, 100 feet above Siberia's Berezovka River in 1900. A year later an expedition, led by Dr. Otto F. Herz, painstakingly excavated the frozen body and transported it to the Zoological Museum in St. Petersburg, Russia.

Much of the head, which was sticking out of the bank, had been eaten down to the bone by local wolves and other animals, but most of the rest was perfect. Most important, however, was that the lips, the lining of the mouth and the tongue were preserved. Upon the last, as well as between the teeth, were portions of the animal's last meal, which for some almost incomprehensible reason it had not had time to swallow. The meal proved to have been composed of delicate sedges and grasses.

Another account states that the mammoth's "mouth was filled with grass, which had been cropped, but not chewed and swallowed" (A. S. W., Nature, Vol. 68, July 30, 1903, p. 297). The grass froze so rapidly that it still had "the imprint of the animal's molars" (Lister & Bahn, Mammoths: Giants of the Ice Age, p. 74). Hapgood's translation of a Russian report mentions eight well-preserved bean pods and five beans found in its mouth (Charles H. Hapgood, The Path of the Pole, 1970, p. 267).

Twenty-four pounds of undigested vegetation were removed from the Berezovka mammoth and analyzed by the Russian scientist, V. N. Sukachev. He identified more than forty different species of plants: herbs, grasses, mosses, shrubs, and tree leaves. Many no longer grow that far north; others grow both in Siberia and Mexico. Dillow draws several conclusions from these remains:

- The presence of so many varieties [of plants] that generally grow much to the south indicates that the climate of the region was milder than that of today.

- The discovery of the ripe fruits of sedges, grasses, and other plants suggests that the mammoth died during the second half of July or the beginning of August (Joseph C. Dillow, The Waters Above: Earth's Pre-Flood Canopy, 1981, pp. 371-377).

An estimated FIVE MILLION mammoths lie entombed in Arctic soils

The soil of Siberia is so full of mammoth bones that ivory mines were working for many years, and at least 20,000 tusks were taken from one mine alone. Besides mammoths, the Arctic soils contain the remains of over 60 animal species, including the woolly rhinoceros. camels, horses, tigers, and antelopes. Many of them lie in frozen silt, mixed together with boulders and tree roots.If we look for the bones and ivory of the mammoth, not just preserved flesh, the number of discoveries becomes enormous, especially in Siberia and Alaska. Nikolai Vereshchagin, the Chairman of the Russian Academy of Science's Committee for the Study of Mammoths, estimated that more than half a million tons of mammoth tusks were buried along a 600-mile stretch of the Arctic coast alone (John Massey Stewart, "Frozen mammoths from Siberia Bring Ice Ages to Vivid Life," Smithsonian, 1977, p. 68). Since the typical tusk weighs 100 pounds, this implies that more than five million mammoths lived in this small region. Even if this estimate is high and represents thousands of years of accumulated remains, we can see that large herds of mammoths must have thrived along the Arctic coast. Many more existed elsewhere. Mammoth bones and ivory are also found throughout Europe, North and Central Asia, in North America, and as far south as Mexico City.

This area of the Arctic coast may well contain the highest density of mammoth remains, since the rich New Siberian Islands lie offshore. The coastal zone of the Laptev Sea, which includes the western area of Vereshchagin’s estimate, is regarded as one of the largest mammoth cemeteries in the world.

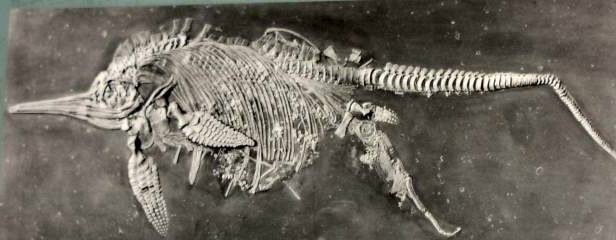

a frozen mammoth in the Siberian permafrost

Scientists expect the reproduction of the mammoth by a genetic material taken from it. (Haveeru Daily 2011/1/24)http://www.haveeru.com.mv/english/details/33895

Dense concentrations of mammoth bones, tusks, and teeth are also found on remote Arctic islands. Obviously, today's water barriers were not always there. Many have described these mammoth remains as the main substance of the islands. Even if these reports are exaggerated, what could account for any concentration and preservation of bones and ivory on barren islands well inside the Arctic Circle? More than 200 mammoth molars were dredged up with oysters from the Dogger Bank in the North Sea.

Oil prospectors, drilling through Alaskan muck, have "brought up an 18-inch (46cm) long chunk of tree trunk from almost 1,000 feet (304.8m) below the surface. It wasn't petrified -- just frozen" (Anonymous, "Much About Muck," Pursuit, Vol. 2, pp. 68-69). The nearest forests are hundreds of miles away. Elsewhere, Williams describes similar discoveries in Alaska:

"Though the ground is frozen for 1,900 feet (580m) down from the surface at Prudhoe Bay, everywhere the oil companies drilled around this area they discovered an ancient tropical forest. It was in frozen state, not in petrified state. It is between 1,100 and 1,700 feet (335m-518m) down. There are palm trees, pine trees, and tropical foliage in great profusion. In fact, they found them lapped all over each other, just as though they had fallen in that position" (Lindsey Williams, The Energy Non-Crisis, 2nd. Edition, 1980, p. 54).

Fossil Forest, Kolyma River

Here, driftwood is at the mouth of the Kolyma River, on the northern coast of Siberia. Today, no trees of this size grow along the Kolyma. Leaves, and even fruit (plums), have been found on such floating trees. One would not expect to see leaves and fruit if these trees had been carried far by rivers. Why didn’t these trees decay?

Widespread freezing and rapid burial are also inferred when commercial grade ivory is found. Ivory tusks, unless frozen and protected from the weather, dry out, lose their animal matter and elasticity, crumble, crack, and become useless for carving. The trade in mammoth ivory has prospered since at least 1611 over a wide geographical region, from which an estimated 96,000 mammoth tusks have been exported. Therefore, the extent of the freezing and burial is wider than most people have imagined.

In May 1846, a surveyor named Benkendorf and his party were camped in Siberia on the Indigirka River. The spring thaw and the unusually heavy rains caused the swollen river to erode a new channel. Benkendorf noticed a large object bobbing slowly in the water. As the "black, horrible, giant-like mass was thrust out of the water [they] beheld a colossal elephant's head, armed with mighty tusks, with its long trunk moving in an unearthly manner, as though seeking something lost therein." They tried to pull the mammoth to shore with ropes and chains but soon realized that its hind legs were anchored, actually frozen, in the river bottom in a standing position.

Twenty-four hours later, the river thawed and eroded the river bottom, freeing the mammoth. The team of fifty men and their horses pulled the mammoth onto dry land, twelve feet from the shore. The 13-foot tall, 15-foot long beast was fat and perfectly preserved. Its "widely opened eyes gave the animal an appearance of life, as though it might move in a moment and destroy [them] with a roar" (William T. Hornaday, Tales from Nature's Wonderlands, 1926.

Translated from the Russian report). They removed the tusks and opened its full stomach containing "young shoots of the fir and pine; and a quantity of young fir cones, also in a chewed state..." (ibid.) Hours later and without warning, the river bank collapsed, because the river had slowly undercut the bank. The mammoth was carried off toward the Arctic Ocean, never to be seen again.

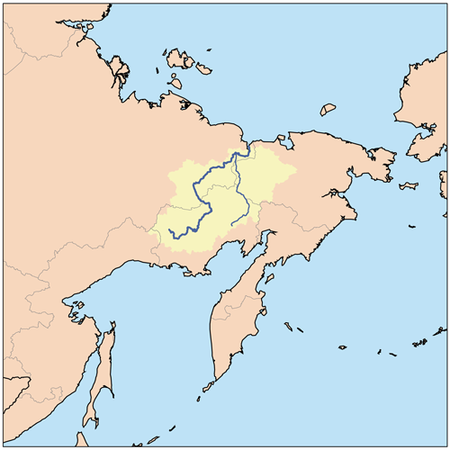

The mammoths covered a wide geographical area

We should also notice the broad geographical extent over which these strange events occurred. They were probably not separate, unrelated events. As Sir Henry Howorth stated:"The instances of the soft parts of the great pachyderms being preserved are not mere local and sporadic ones, but they form a long chain of examples along the whole length of Siberia, from the Urals to the land of the Chukchis [the Bering Strait], so that we have to do here with a condition of things which prevails, and with meteorological conditions that extend over a continent.

"When we find such a series ranging so widely preserved in the same perfect way, and all evidencing a sudden change of climate from a comparatively temperate one to one of great rigor, we cannot help concluding that they all bear witness to a common event. We cannot postulate a separate climate cataclysm for each individual case and each individual locality, but we are forced to the conclusion that the now permanently frozen zone in Asia became frozen at the same time from the same cause" (Henry H. Howorth, The Mammoth and the Flood, 1887, p. 96).

Actually, northern portions of Asia, Europe, and North America contain "the remain of extinct species of the elephant [mammoth] and rhinoceros, together with those of horses, oxen, deer, and other large quadrupeds" (A. G. Maddren, "Smithsonian Exploration in Alaska in Search of Mammoth and Other Fossil Remains," Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections, Vol. 49, 1905, p. 87). So the event may have been even more widespread than Howorth believed.

"There are some cases of finds of not only dead mammals, but also fishes, unfortunately lost for science. In 1942, during road construction in the Liglikhtakha River valley (the Kolyma Basin) an explosion opened a subterranean lens of transparent ice encasing frozen specimens of somebig fishes. Apparently the explosion opened an ancient river channel with representatives of the ancient ichthyological fauna [fish]. The superintendent of construction reported the fishes to be of amazing freshness, and the chunks of meat thrown out by the explosion were eaten by those present" (Y. N. Popov, “New Finds of Pleistocene Animals in Northern USSR,” Nature, No. 3, 1948, p. 76).The second report comes from M. Huc, a missionary traveler in Tibet in 1846. Sir Charles Lyell, often called the “father of geology,” also quoted this same story in the 11th edition of his Principles of Geology. After many of Huc’s party had frozen to death, survivors pitched their tents on the banks of the Mouroui-Oussou (which lower down becomes the famous Blue River). Huc reported:

"At the moment of crossing the Mouroui-Oussou, a singular spectacle presented itself. While yet in our encampment, we had observed at a distance some black shapeless objects ranged in file across the great river. No change either in form or distinctness was apparent as we advanced, nor was it till they were quite close that we recognized in them a troop of the wild oxen. There were more than fifty of them encrusted in the ice.

No doubt they had tried to swim across at the moment of congelation [freezing], and had been unable to disengage themselves. Their beautiful heads, surmounted by huge horns, were still above the surface; but their bodies were held fast in the ice, which was so transparent that the position of the imprudent beasts was easily distinguishable; they looked as if still swimming, but the eagles and ravens had pecked out their eyes" (M. Huc, Recollections of a Journey through Tartary, Thibet [Tibet], and China, During the Years 1844, 1845, and 1846. Vol. 2 (New York: D. Appleton & Co., 1852), pp. 130-131).

No comments:

Post a Comment